A worker on a an oil drill near New Town, North Dakota.

Daniel Acker | Bloomberg | Getty Images

The oil market is already struggling with too much supply, and the U.S. is about to flood the world with a lot more.

In the last decade, the U.S. has more than doubled oil production to 12.3 million barrels a day, making it the world’s largest producer. But the infrastructure needed to transport that crude out of Texas oil fields and onto the world market has been lacking.

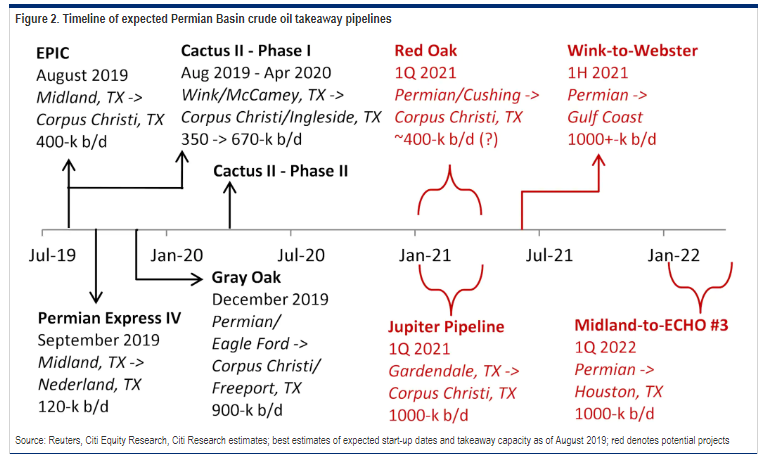

This month marks a big change for the industry with the start of the Plains All American Pipeline’s Cactus II, a 670,000 barrel a day pipeline, connecting the Permian Basin to Corpus Christi, Texas, and from there to the world. That pipeline, and another, named Epic, are just the start, with more to follow.

The new pipelines are expected to take more Texas crude to the Gulf Coast, and from there it can be shipped out to the world, but the world is now well supplied, and even more U.S. oil could help depress prices, especially if the trade wars continue to suppress demand.

According to Citigroup, the new pipelines could help grow U.S. oil exports from the current 3 million barrels a day by 1 million barrels more by year-end and another million barrels next year. Exports have already grown by an average 970,00 barrels a day this year over last year, according to Citigroup.

Source: Citigroup

“It will be 4 million barrels a day by six or eight months. Four million barrels a day is a lot bigger than the North Sea as a whole. That crude oil is going to go everywhere. It goes to Asia, Europe, to India,” said Edward Morse, Citigroup global head of commodities research. “If the U.S. gets to 6 million barrels a day in three years, it will be hands-down the world benchmark.”

The surge in pipeline capacity will help unlock a bottleneck of oil in the Permian Basin, which Citi has forecast could double its production to about 8 million barrels a day by 2023.

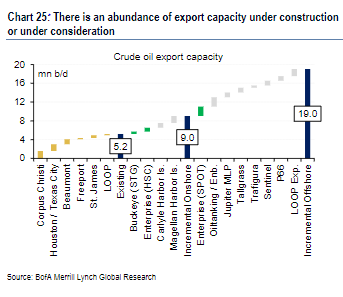

As the pipelines are being built, there will be a need for increased export capacity. Shipping facilities are being expanded all along the Gulf Coast, in Texas and in Louisiana. The U.S. will soon have the export capacity for 6 million barrels a day, and even more is planned, according to Citi.

“Until now, it’s been an issue of getting oil from the Permian down to the Gulf Coast. Now it’s going to be getting out of the Gulf Coast to the world market,” said Francisco Blanch, head of Bank of America commodities and derivatives research. “The ability to move all that oil is going to improve over the course of the next 18 months.”

Source: Bank of America Merrill Lynch

New world order?

All of this new oil creates a dilemma for OPEC. Saudi Arabia, de facto leader of OPEC, and its partner Russia, have cut back on oil production to help stabilize prices. Even with the loss of much of Venezuela’s oil and 2 million barrels a day from Iran, there is plenty of oil with U.S. oil production growing at more than 1 million barrels a day this year and demand growing at about the same pace.

“OPEC has lost 1% of market share per annum, every year for the last seven years,” said Blanch.

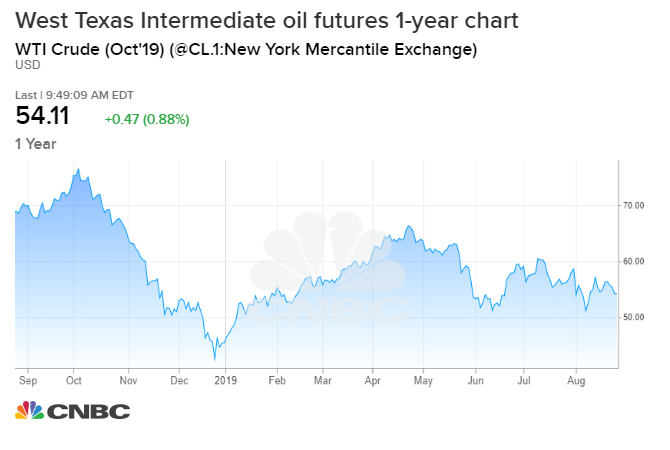

Oil prices have been range bound, with West Texas Intermediate crude futures well off the one-year high from October of $75 per barrel. The price fell to a low of $42 on Christmas Eve, as risk markets sold off, and has been in the mid-$50s lately. Brent futures, the international benchmark, has traded on both sides of $60 per barrel this month.

While OPEC has intentionally curbed production, simple economics have contained U.S. production growth, which has been flattish in recent weeks, after rising from 11 million barrels a day a year ago.

“Obviously, companies are cutting back. They’re cutting back in terms of investment and activity. You see the rig count coming down. You still see production efficiencies driving growth, but you’ll have a slower rate of sequential growth from here,” said Blanch. He noted that U.S. rig count was down 12% from year-ago levels at the middle of August.

Morse said he expects Russia and OPEC to stay together, and an economic slowdown would encourage them to continue their partnership.

“A recession scenario makes it easier for them to believe in what they’ve been saying,” he said, noting the producers have held oil from the market to stabilize supplies.

When demand drops, prices fall and U.S. producers would no longer find it makes economic sense to pump as much oil. An economic downturn would only slow the trend, not stop it.

“We agree there’s going to be an overabundance for the next two to three years. We see prices being challenged for the next two to three years. We see Brent in the low $50s, and WTI in the high $40s, which is not an environment where there’s going to be much as much reinvestment, as there is,” Morse said. “We’ll have to modify our expectations for production growth, given the increased likelihood that global GDP is going to be low and even without a recession, demand will be lower.”

US crude as the benchmark?

Even if there is a more significant slowdown, the U.S. will continue to move toward a more dominant role in the world oil market, with each barrel that comes out of the Gulf Coast. Morse said the U.S. emergence as a bigger exporter could change the world market’s focus and a Gulf Coast-based crude price could become the global benchmark at some point, replacing Brent.

The spread between the price of Brent oil and WTI has gotten closer together, as more U.S. oil goes on to the world market. European Brent is about $5 more per barrel but it has been a double-digit spread between the two.

Morse said the U.S. is on its way to becoming a net exporter. It already exports diesel, gasoline and other fuels. According to weekly government data, the U.S. two weeks ago exported 5.3 million barrels of refined products and 2.8 million barrels a day of oil.

“Add on the amount of petroleum products that are exported and add on the amount of natural gas that is exported. The U.S. becomes the biggest hub for energy trading in the world,” said Morse. “It has dramatic implications for the U.S. dollar.”

Morse notes there are those who doubt the dollar’s future as the global reserve currency. But in a scenario where the U.S. grows into an energy powerhouse, “the dollar becomes more entrenched.”

The U.S. had been the world’s dominant oil producer, prior to World War II. “This will be back to the future for the Gulf Coast,” said Daniel Yergin, IHS Markit Vice Chairman. Yergin said the U.S. would not have had the opportunity to increase production as much, were the law not changed in 2015 to allow for U.S. oil exports.

“If they didn’t lift that ban, it would have capped U.S. oil production because the system couldn’t absorb all that light sweet crude,” said Yergin.

The U.S. continues to import crude oil and refined products. South Korea has become the largest buyer of U.S. crude, at 650,000 barrels a day, according to Citigroup. It is followed by Europe, Canada, India and China, which has cut back.

“There was the great historic shift from the U.S. Gulf of Mexico to the Persian Gulf. Now, there’s not a complete shift but a rebalancing in which the U.S. Gulf Coast has once again become of the world’s largest sources of crude oil and products,” said Yergin.

Hurricane Alley

As the U.S. exports more oil, the market’s focus will be on the Gulf Coast’s vulnerability during hurricane season. The industry has built refineries and rigs that can withstand strong hurricanes, but even a Category 1 storm, like Barry earlier this year, disrupts operations as rigs are shut in ahead of a storm.

“The hurricane risk to the global supply chain is increasing exponentially as more U.S. crude oil gets embedded in the system,” said John Kilduff of Again Capital. “It will add to price volatility, but it would have to be an extreme circumstance for U.S. supplies to be disrupted for a prolonged period.”

Kilduff said a major outage of Gulf operations would likely be rare. “You would need a Rita, Katrina situation, where the pipelines were damaged and there were extended outages,” he said.

Shale Endurance

The shape of the U.S. shale industry has changed with the arrival of oil majors in the last several years.

The oil industry in Texas was once made up of wildcatters and small operators. But even the bigger independents could go from bust to boom when oil prices swung in the past.

Now the oil drillers are being held accountable to their shareholders, and they are being forced to be much more prudent, even when oil prices are higher.

The arrival of the majors in the field has brought in companies that are operating on scale and have a foothold in other sectors of the industry, like offshore or natural gas. Both Chevron and Exxon Mobil announced major Permian expansions this year.

“They’re not as easily flushed out,” said Kilduff.

Morse said the transformation of the industry is significant.

“The structure of the industry belies the thinking of the skeptics, those who said this was a flash in the pan,” said Morse.